source Vie Nouvelle.

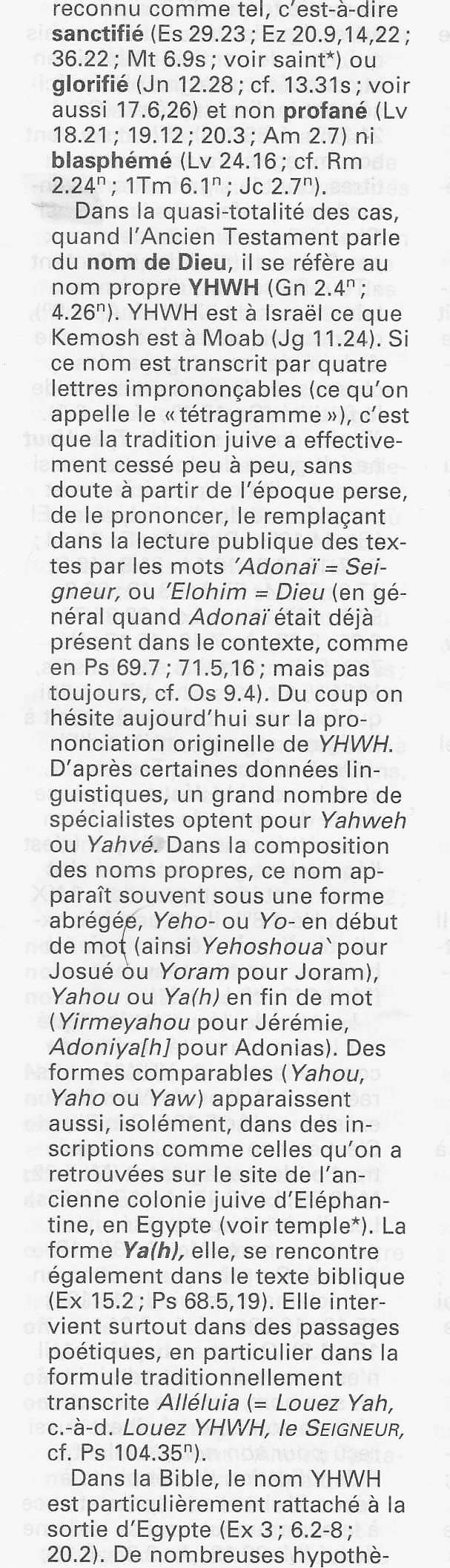

C'est étrange dans les pays alentour d'Israël les gens donne des noms a leurs dieux locaux et paradoxalement chez les juifs Dieu n'aurait pas de nom propre!

Vous n'êtes pas connecté. Connectez-vous ou enregistrez-vous

Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 23 Mai - 10:26

Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 23 Mai - 10:26

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 23 Mai - 16:43

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 23 Mai - 16:43

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 6 Juin - 11:32

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 6 Juin - 11:32 Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 9 Juin - 9:37

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 9 Juin - 9:37 Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 9 Juin - 18:03

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 9 Juin - 18:03

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 13 Juin - 8:53

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 13 Juin - 8:53

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mer 27 Juil - 17:42

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mer 27 Juil - 17:42 Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 25 Oct - 10:30

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 25 Oct - 10:30

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 15 Nov - 16:08

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 15 Nov - 16:08 Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 3 Déc - 16:03

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 3 Déc - 16:03

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 29 Déc - 15:39

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 29 Déc - 15:39

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Dim 15 Jan - 17:30

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Dim 15 Jan - 17:30 Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 20 Mar - 14:32

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 20 Mar - 14:32 Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 21 Mar - 11:17

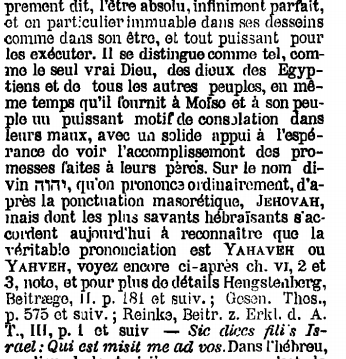

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 21 Mar - 11:17Mais que si!Invité a écrit:Mais "Jéhovah" ; "Yahwé ; "YHWH", ne sont pas des synonymes

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Ven 9 Juin - 16:35

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Ven 9 Juin - 16:35 Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Ven 23 Juin - 11:58

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Ven 23 Juin - 11:58 Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 26 Juin - 9:16

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 26 Juin - 9:16 Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 26 Juin - 10:17

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 26 Juin - 10:17

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 25 Juil - 8:28

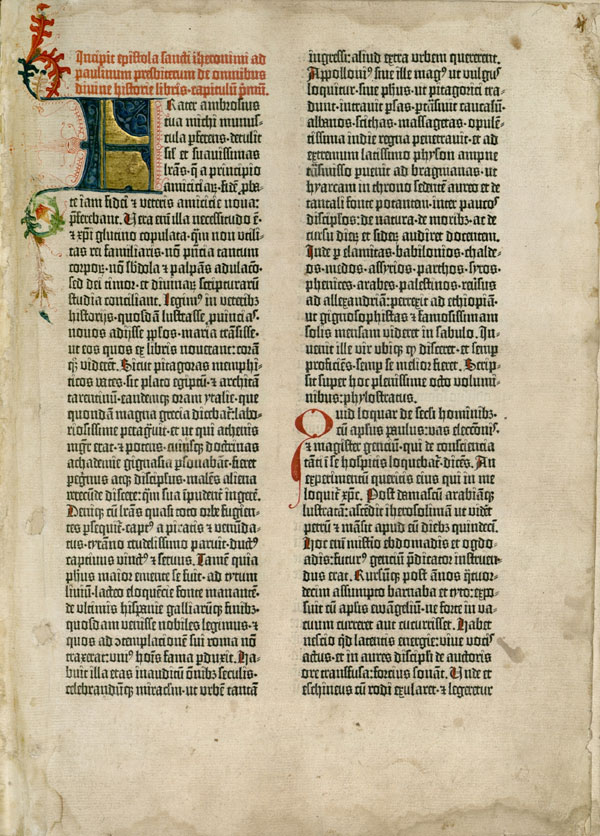

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 25 Juil - 8:28La Bible chrétienne, Nouveau Testament: le Nouveau Testament de Notre Seigneur et Sauveur Jésus, le Christ: traduction du grec, principalement du Codex Sinaïticus et le Codex Vaticanus, ceux-ci étant la plus ancienne mss et la plus complète. du Nouveau Testament

Auteur : George Newton LeFevre

Éditeur: Strasbourg, Pa. GN LeFevre, 1928.

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 29 Juil - 0:00

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 29 Juil - 0:00

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 29 Juil - 8:10

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 29 Juil - 8:10 Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 29 Juil - 12:22

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 29 Juil - 12:22

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 29 Juil - 15:07

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 29 Juil - 15:07En français je ne sais pas.Mikael a écrit:Existe t-il d'autres bibles catholiques qui utilisent le nom de Jéhovah ?

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 29 Juil - 19:32

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Sam 29 Juil - 19:32

Oui, sans problème. Le pape François ne veut plus en entendre parler, alors on en trouve dans des couvents, des monastères, pour futurs séminaristes puisqu'elles sont oubliées et mises en vente pour trois fois rien, après restauration. J'ai acheté une Bible de Carrières avec Jéhovah, du XVII siècle, cuir et reliures refaites, complète en 24 volumes, pour 60€. Et une autre avec l'hébreu à 10€.Mikael a écrit:Existe t-il d'autres bibles catholiques qui utilisent le nom de Jéhovah ?

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Dim 30 Juil - 7:51

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Dim 30 Juil - 7:51

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Dim 30 Juil - 10:24

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Dim 30 Juil - 10:24

Sois sérieux un instant, merci. Je ne vais pas scanné des dizaines de pages sur le nom CATHOLIQUE LATIN de יהוהMikael a écrit:Et que disent les commentaires sur le nom de Dieu ?

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 31 Juil - 8:17

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 31 Juil - 8:17

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 31 Juil - 10:12

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 31 Juil - 10:12

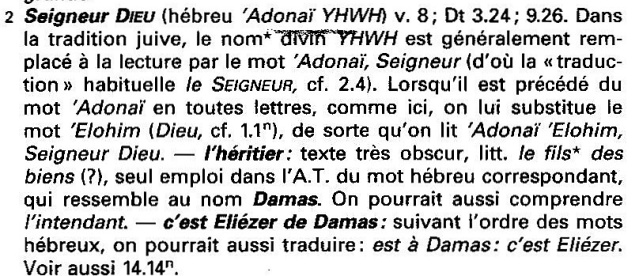

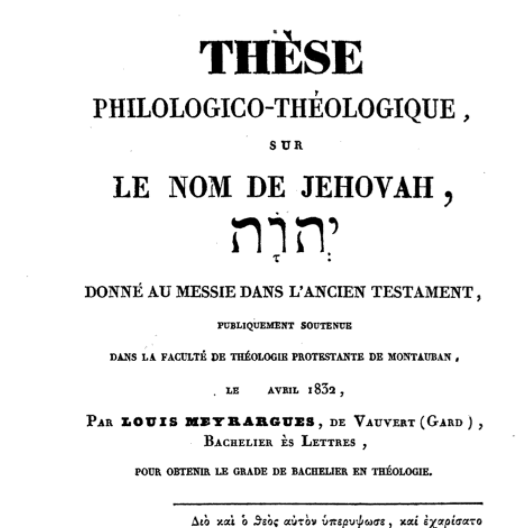

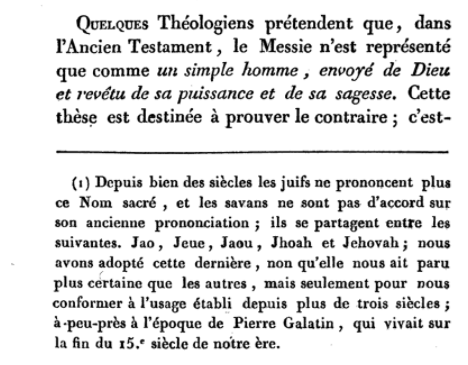

Jehovah est du latin médiéval du 13e siècle inventé par le dominicain ibère Raymundus Martini.Mikael a écrit:Mais je suis sérieux, c'est pour me renseigner que j'ai posé la question.

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 31 Juil - 11:31

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 31 Juil - 11:31

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 31 Juil - 21:31

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Lun 31 Juil - 21:31

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 1 Aoû - 7:36

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 1 Aoû - 7:36

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 1 Aoû - 7:38

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 1 Aoû - 7:38

Non, cela fait partie de bibliothèques privées. C'est patrimoine catholique.Mikael a écrit:Cette traduction existe t-elle en ligne ?

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 1 Aoû - 7:40

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mar 1 Aoû - 7:40

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 28 Sep - 21:09

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 28 Sep - 21:09

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mer 4 Oct - 13:48

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Mer 4 Oct - 13:48

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 10:19

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 10:19

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 10:37

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 10:37Il n'y a pas que les rabbins car les traducteurs de la bible catholiques ou protestants ont fait de même.philippe83 a écrit:Eh oui comme vous le constatez certains sont capable de tout pour trouver des excuses au sujet de la prononciation du Nom de Jéhovah. Ah ces rabbins sont vraiment roublard vous trouvez pas?

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 14:14

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 14:14

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 15:33

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 15:33

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 16:08

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 16:08

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 16:38

Re: Jéhovah dans la Bible Jeu 5 Oct - 16:38

Quoi que.Marmhonie a écrit:Ne dérapez pas non plus, Jéhovah est la latinisation catholique romaine du Non divin

Sujets similaires

Permission de ce forum:

Vous ne pouvez pas répondre aux sujets dans ce forum